By Mike Webb, Sonoma State University

webbmi@sonoma.edu

This paper will examine sensory integration’s impact on behavioral, emotional, and motor regulation. Specifically, the focus will be on the role of the vestibular and proprioceptive systems. Identifiers of dysregulation and strategies to support modulation will also be discussed. These strategies include guidelines for designing a sensory-based adapted physical education program.

We all feel confident and connected to ourselves and those around us. When we live with autism, intellectual disabilities, and developmental disabilities, sensory differences occur. How do we support people in the Disability Community to develop emotional well-being and confidence in movement patterns? Sensory integration is an unconscious process where sensations are organized and used to develop motor, cognitive, and social skills effectively. The more accurately the sensory system can integrate incoming stimuli, the likelihood of appropriate behavioral, emotional, and motor responses increases.

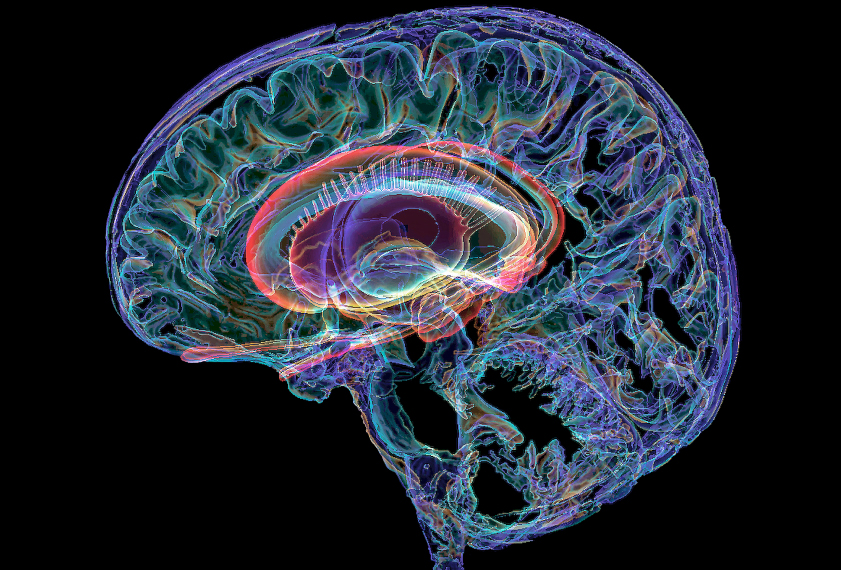

We are familiar with the senses of vision, taste, touch, and smell, but let us consider two lesser-known sensory systems: vestibular and proprioception. “The vestibular system is a bony structure located on the right and left sides of the skull near the hearing center. The vestibular system acts as an inertial guidance device, continually reporting information about the motions and position of the head and body to integrative centers located in the brainstem, cerebellum, and somatic sensory cortices.”[1] The vestibular system contributes to muscle tone, coordination, balance, ocular-motor, arousal, and emotional state.[2] When vestibular input is not adequately processed, a student will seek specific vestibular input such as rocking, spinning, balance activities, auditory input, and swinging to regulate.

Proprioception is informed by receptors located in the skin, muscles, and tendons. “Proprioception is position sense – a continuous, internal awareness of the body’s posture and movement sense – awareness of body parts and their location at all times.”[3] Proprioception provides feedback for the rate and timing of movements, the force exerted by muscles, changing angles at each joint, and the body’s orientation in space.[4] When proprioceptive processing is suboptimal, students will find other avenues for input, including hitting, pushing, hand flapping,[5] bumping into furniture or people, biting, chewing, and wearing heavy or tight clothing (regardless of weather) and tight hugs.

When vestibular and proprioception integration dysfunction are evident, the brain either underreacts or overreacts to input. The limbic system, located in cortical, subcortical, and brainstem areas, plays a role in influencing behavior.[6] When the limbic system does not receive accurate information from the sensory system, there is a plausibility that a student will experience fear, anger, and sadness.[7]When a student can not rely on the body’s signals, uneven development may occur in “play, social participation in adulthood,” [8] relationship styles and ability to cope,[9] and gross motor development.

Emotional, behavioral, and motor intervention primarily focus on the prefrontal cortex, which regulates our thoughts, actions, and emotions through extensive connections with other brain regions.[10] Goal-directed behavior, such as emotional regulation and efficient motor skills, can only be developed once subcortical needs are met.[11] In other words, until students have a sense of where their body is in space and feel safe, more complex skills cannot be established. Subcortical structures include the cerebellum and brain stem and do not respond to words and reason like the prefrontal cortex but to sensory input. Therefore, to enhance behavioral, emotional, and motor regulation, adapted physical education programs must intentionally incorporate vestibular and proprioceptive input in each session.

For an adapted physical education instructor, this would mean frontloading lessons with vestibular and proprioception input before practicing locomotor or ball control skills. For example, equipment that would activate the vestibular attributes of balance, muscle tone and coordination, proprioceptive attributes of force exerted by muscles, rate and timing of movement would include medicine balls, battle ropes, plyometric benches, bands, scooter boards, play dough, and light hand weights. Activities should have minimal motor planning, a visually clear exercise area, and linear patterns. These guidelines ensure maximum vestibular and proprioceptive input, promoting improved muscle tone, coordination, movement sense, and emotional regulation.

Emotional regulation is especially supported in a structured, sensory-based format because vestibular input releases the neurochemical histamine, an excitatory response, meaning students will be more energized, and proprioceptive input releases the neurochemical serotonin, which helps students to feel safe and in control.[12]

“Agency refers to the sense that we are in control of our body, thoughts, and actions.”[13]When students are dysregulated, they seek agency by self-stimming, withdrawing[14] or behavior outbursts. The foundation of agency is interoception, a process in which “bodily signals are interpreted, integrated, and regulated from within itself.”[15] Interoception is supported by sensory input, in particular, proprioception.[16] A proactive, structured, sensory-rich, adapted physical education program will refine movement patterns and aid the development of agency and interoception. The more students develop a “friendly relationship”[17] with their bodies and learn to trust their body signals, the likelihood of living with enhanced agency, play, and socialization[18] increases.

[1] Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al., editors. Neuroscience. 2nd edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2001. Chapter 14, The Vestibular System. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10819/

[2] Williamson, G. G., & Anzalone, M. E. (2001). Sensory Integration and Self-Regulation in Infants and Toddlers: Helping Very Young Children Interact With Their Environment (pp. 7-8). Zero to Three: National Center for Infants, Toddlers and Families.

[3] Williamson, G. G., & Anzalone, M. E., 9.

[4] Williamson, G. G., & Anzalone, M. E., 9.

[5] Mauro, T., & Cermak, S. A., Ed.D.,OTR/L, FAOTA (2006). The Everything Parent’s Guide To Sensory Integration Disorder: Get the right diagnosis, understand treatments, and advocate for your child. F+W Publications, Inc.

[6] Sokolowski K, Corbin JG. Wired for behaviors: from development to function of innate limbic system circuitry. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012 Apr 26;5:55. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00055. PMID: 22557946; PMCID: PMC3337482.

[7] Ayers, A. J., Ph.D, (2005). Sensory Integration and the Child: Understanding hidden sensory challenges, 25th anniversary edition. Western Psychological Services.

[8] Bundy, A. C., & Lane, S. J. (2020). Sensory Integration: Theory and practice (-3rd ed.). F.A. Davis Company.

[9] Jerome, E.M., & Liss, M. (2005). Relationships between sensory processing style, adult attachment, and coping. Personality and Indivudual Differences, 38(6), 1341 -1352. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.08.016

[10] Arnsten AF. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009 Jun;10(6):410-22. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648. PMID: 19455173; PMCID: PMC2907136.

[11] Ayers, A. J., PhD., OTR, FAOTA, Hanschu, B., OTR/L, & Clopton, H., OTR/L (n.d.). Feeding the Brain Pyramid. Retrieved September 6, 2019, from https://www.developmental-delay.com/page.cfm/383

[12] The Science Behind Sensory Processing. (n.d.). Understood. Retrieved from https://www.riseot.com/post/the-science-behind-sensory-processing

[13] Costandi, M. (2022). Body am I: The new science of self-consciousness (p. 91). MIT Press.

[14] Roberts JE, King-Thomas L, Boccia ML. Behavioral indexes of the efficacy of sensory integration therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 2007 Sep-Oct;61(5):555-62. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.5.555. PMID: 17944293.

[15] Chen WG, Schloesser D, Arensdorf AM, Simmons JM, Cui C, Valentino R, Gnadt JW, Nielsen L, Hillaire-Clarke CS, Spruance V, Horowitz TS, Vallejo YF, Langevin HM. The Emerging Science of Interoception: Sensing, Integrating, Interpreting, and Regulating Signals within the Self. Trends Neurosci. 2021 Jan;44(1):3-16. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.10.007. PMID: 33378655; PMCID: PMC7780231.

[16] (n.d.). What is Interocpetion? Occupational Therapy Helping Children. https://www.occupationaltherapy.com.au/interoception/

[17] Van der Kolk, B. A., M.D. (2014). The Body Keeps The Score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma (p. 99). Penguin Books.

[18] Kim, J. M., & Kim, K. M. (2009). The effects of sensory integration intervention on play in children with sensory modulation disorder. The Journal of Korean Academy of Sensory Integration, 7(1), 1-12.